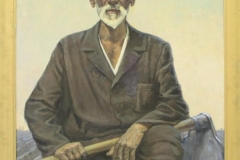

MIRABS

Traditional water managers in Central Asia used to be called “Mirabs.” The profession of “mirab” has disappeared in its traditional understanding from the Central Asian region. The closest parallel today are municipal workers who perform the duties of “mirabs” these days. Traditionally, “mirabs” controlled the flow of water through irrigation canals and ditches, making sure that crops and green areas/pasture were watered on time. Canals running through the village also cooled down the area during hot summers. Mirabs also monitored the timely cleaning of the irrigation canals and sustainable use of water. Skills for this vocation and position were passed down through generations in some families…

The video consists of archival footage of real-life mirabs and interviews with contemporary irrigation specialists

Over the course of a thousand years, the population living along the Syr Darya River has accumulated a rich body of ecological knowledge. This includes traditional knowledge of water, related to local livelihoods dependent on irrigated agriculture. However, the riparian ecosystems have been degrading over the last hundred years.

What elements of traditional ecological knowledge reflect local people’s attitudes towards water and the river? There are local fairy tales, myths, sayings, beliefs, and ceremonies as well as sacred sites such as Hubbi Ata in the Danghara district of Ferghana Province (Uzbekistan). For example, these are some of the popular proverbs from Ferghana:

Even if your father is mirab, you must clean the ditches to drink water

(Отанг мироб бўлса ҳам, Ариқни тозалаб сув ич).

One person digs the irrigation canal and thousands benefit from it.

(Бир киши ариқ қазир, Минг киши ундан сув ичар).

An ear is a mother for speach, a spring is a mother for water.

(Гапнинг онаси — қулоқ, Сувнинг онаси — булоқ).

The coming of spring increases the amount of water in a river, a hard work increases the amount of respect a man has.

(Дарё сувини баҳор тоширар, Одам қадрини меҳнат оширар).

Earth is mother, water is father, the earth is a treasure, water is a pearl.

(Ер — она, сув — ота, Ер — хазина, сув — гавҳар.

Master of land is God, the master of water is the king.

(Ер оғаси — худо, Сув оғаси — султон).

A person’s life is a river.

(Инсон умри — дарё суви).

One can learn about this traditional knowledge from mirabs (water regulators), farmers, fishermen, hunters, traditional doctors, and local elders. Islam as the locally dominant religion also encourages the sustainable use of water. Yet, there are intergenerational differences in views towards the Syr Darya River. The older generation tends to view the river as “sacred”, “secretive”, the “mother river” or “great river”. In a broader sense, water is often described as “cleansing” and “healing” and is seen as a remedy for various illnesses.

Younger people however tend to be unaware of those beliefs or have a vague understanding of them. The locals connect young people’s lack of awareness of water-related beliefs with a general loss of‘ ecological knowledge and the declining water levels of the Syr Darya since the 1980s. Moreover, since the 1980s the river is no longer used as a source of tap water, but rather solely for irrigational purposes.

To transmit the beliefs and views on water and foster a broader “ecological culture” (which implies keeping the river, streams, and canals clean), local entrepreneurs and farmers organize competitions and games for young people. In general, the local water-related knowledge and beliefs in the Fergana Valley can be grouped into symbolic beliefs (purity, cleansing, healing, etc). and utilitarian knowledge (i.e. irrigation practices).

There is also a tradition of naming children after the Syr Darya river. Such names as Syrdaria, Sayhun, or Daria are common in the Fergana valley. There are also names related to the villages located on the Syr Darya banks such as Tepekurghan (a village in Pap District), Kalghandarya (a village in Mingbulak District).